Life Goes On—Imperfect and Unresolved

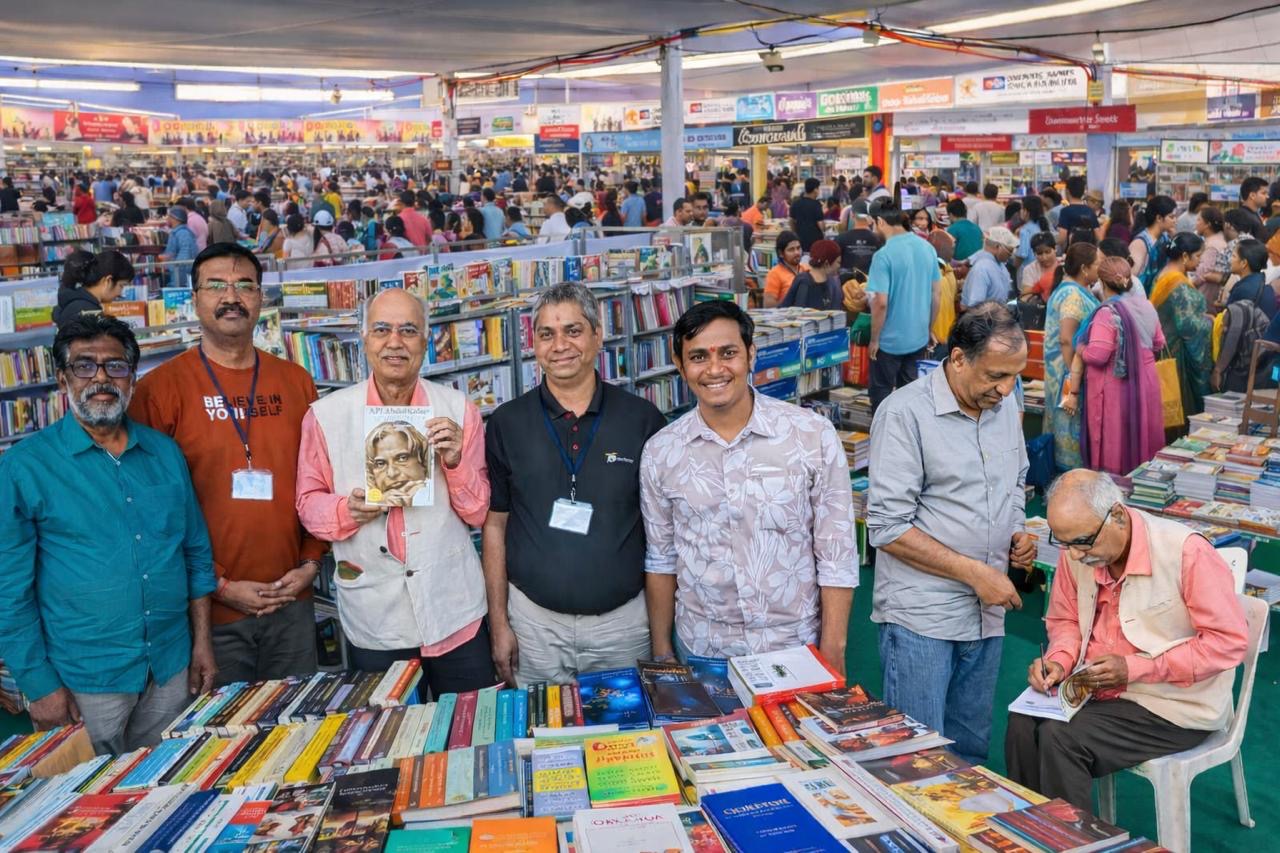

The readers have lapped up the silver jubilee edition of Wings of Fire. Within a month of its release on October 15, 2025, the 94th birth anniversary of Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, the first print was sold out. At the 38th Hyderabad Book Fair, on December 20th, 2025, I saw people buying this book, and was pleasantly surprised when one of them approached me for an autograph after recognising me. He asked me what the best passage I would like him to read was, and I unhesitatingly pointed out a poem on page 130 that Dr Kalam had quoted.

God hath not promised

Skies always blue,

Flower-strewn pathways

All our lives through…

These lines are from a well-known hymn composed by Annie Johnson Flint (1866-1932), who lost both parents in her early childhood and endured a severe form of arthritis all her life.Dr Kalam’s ascent in life, too, was neither easy nor accidental; it was earned through struggle and steadfast perseverance. This hymn serves as a gentle reminder against modern impatience. The lines quietly but firmly remind us that struggle is not an interruption to life; it is part of its design.

We live in an age that constantly promises the opposite. Technology assures us of solutions. Markets promise prosperity. Politics promises justice. Social media promises happiness, visibility and belonging. Yet beneath these assurances run a deepening and widening disquiet: inequality grows, money consolidates power, violence seeps into homes and public spaces, consumerism replaces meaning, and the elderly—once custodians of wisdom—are increasingly treated as surplus.

Life never fully resolves itself, yet it goes on. This tension—between the desire for neat endings and the reality of unresolved living—centralises Shakespeare’s troubling comedy, All’s Well That Ends Well. Despite its optimistic title, the play provides no easy consolation. It gestures toward closure while quietly denying it, leaving the audience unsettled rather than reassured. People adjust, endure, rationalise and hope—often without complete resolution.Shakespeare seems to suggest that the real triumph is not the arrival at a perfect ending. The stubborn persistence of life itself makes people carry on.

The play, written around 1604–1605, recounts the story of Helena, a poor yet intelligent young woman who loves the nobleman Bertram. After curing the King of France with her medical skill, Helena is rewarded with the right to choose a husband and selects Bertram. But high-headed Bertram rejects her and imposes seemingly impossible conditions for accepting her as his wife. Through perseverance, disguise and clever strategy, Helena fulfils these conditions. The play examines love, merit versus birth, female agency and moral ambiguity. Helena wins her right over Bertram, but without his repentance and reconciliation. It is a conditional ending—legally complete and socially acceptable, yet emotionally and morally unsettled.

Shakespeare gave the English language nearly 2,000 enduring words and phrases that are still actively used in the modern world—for example, the ubiquitous word ‘manager,’ used in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act V, Scene I

Come now; what masques, what dances, shall we have,

To wear away this long age of three hours

Between our after-supper and bedtime?

Where is our usual manager of mirth?

This anxiety, boredom, and discomfort mirror our own age, marked by ‘managing’ situations without resolving issues.Inequality is ‘managed,’ not resolved. Injustice is ‘addressed,’not dismantled. Violence is condemned, yet normalised. Alcohol and smoking are denounced,yet promoted for profit. We are told that things are improving even as lived experience contradicts the narrative—like Shakespeare’s ending of All’s Well That Ends Well, modern life functions, but uneasily.

One of the play’s central conflicts is between merit and birth. The daughter of a low-ranked doctor, Helena rises through intelligence, service and bravery. Bertram resists her not because she lacks virtue, but because she lacks pedigree. The King orders the marriage to proceed. Social order is preserved through power rather than consent. Shakespeare does not disguise the discomfort this creates.

Four centuries later, the names have changed, but the structure remains. The modern world praises meritocracy while quietly safeguarding inherited privilege. Education, capital, influence and networks continue to centralise power, even as the rhetoric of ‘equal opportunity’ grows louder. Success does not guarantee dignity. Competence does not ensure acceptance. The hymn does not promise ‘smooth roads and wide,’ and Shakespeare does not promise justice without resistance.

In the present-day world, there are no longer kings, but money and power increasingly shape outcomes. Markets reward scale, not fairness. Politics values influence over integrity. Institutions function—but often at the cost of human trust.This produces a subtle moral displacement. What works begins to matter more than what is right. What ends well becomes justification enough, even if the means bruise human dignity along the way. Even the hymn does not promise triumph beyond ’strength for the day, rest for the labour.’ In other words, moral life is sustained not by victory, but by endurance.

The play, All’s Well That Ends Well, contains no spectacular bloodshed. Still, it is woven with subtler forms of violence: coercion, humiliation, abandonment, and emotional neglect—Bertram’s cruelty wounds without drawing blood. Helena’s suffering is noble, yet genuine. The modern world remains largely unchanged. There is widespread domestic aggression, emotional abuse, public outbursts, and digital harassment. A world fixated on dominance grapples with vulnerability. A culture that values power tends to forget care.

In All’s Well That Ends Well, Parolles embodies this emptiness—language without substance, performance without courage. He consumes attention but produces nothing of value. His eventual exposure is both comic and instructive. Modern consumer culture produces Parolles at scale. Noise replaces depth. Speed replaces reflection. The hymn quietly resists this frenzy by slowing time—by reminding us that life is not meant to be flower-strewn at every step.

God hath not promised.

Sun without rain,

Joy without sorrow,

Peace without pain…

No wonder the world is imperfect and unresolved. Inequality persists. Power distorts. Violence scars. Consumerism distracts. Elders are forgotten. Life continues—not because it is just or orderly, but because people persist in choosing to endure. Within narrow limits and imperfect conditions, they keep caring, keep hoping, and keep shaping meaning where none is guaranteed. It is this quiet, stubborn human resolve—more than fairness or reward—that allows existence to move forward, one deliberate act of attention and compassion at a time.

‘All’s well,’ not because all is healed, but because life, in its broken continuity, still invites responsibility. Perhaps that is the quiet lesson shared by Shakespeare and the hymn alike: not that the world will become just, gentle or equal overnight—but that even without such promises, we are still called to live wisely, compassionately and faithfully, one unresolved day at a time.

Life, much like the greatest works of literature, seldom reaches neat conclusions. It moves forward with loose ends, half-healed wounds and questions that defy final answers—and yet it continues anyway. To despair because life is imperfect is to misunderstand its deepest rhythm. Meaning is not found in perfect resolution, but in perseverance, compassion and the quiet courage to carry on despite uncertainty.

As All’s Well That Ends Well gently suggests, survival itself can be a form of grace. In moments when clarity fails and outcomes remain unresolved, hope does not disappear; it simply takes on a different form. As the hymn quietly assures us

But God hath promised strength for the day,

Rest for the labor, light for the way,

Grace for the trials, help from above,

Unfailing sympathy, undying love.

And so, life—imperfect and unresolved—continues, not by erasing uncertainty but by bearing it with quiet dignity. At a book fair, a stranger steps forward, book in hand, asking for an autograph—not for possession, but for connection. In that silent exchange lies continuity: ideas passing gently from one life to another. Dr Kalam left this world a decade ago, yet his presence endures in the minds he awakened and the futures he shaped. That is how life transcends its own limits. We live on through what we inspire in others. In that sense, I hope that I,too, will live beyond my life.

MORE FROM THE BLOG

A Scientist and a Gentleman

In every civilisation, there are two measures of success. One is public and noisy—titles, awards, positions, headlines, and the temporary glow of importance. The other is almost invisible: the quality of a human being. History remembers the first for a moment and the...

Learning the Art of Writing by Reading

I enjoy reading quite a lot—sometimes as much as ten hours a day, though on average about eight. Reading has become my primary pastime—not as a leisure activity, but as a discipline. I read good books, chosen carefully, ordered online and added to a personal library...

From Disease to Wellness: Time for a Paradigm Shift

Modern medicine is magnificent at one thing: it rushes heroically to the battlefield after the war has already been lost. When the coronary artery is blocked, a stent is inserted. When the pancreas fails, insulin is administered. When cancer erupts, it deploys...

This really struck a chord. The honesty with which you speak about life moving forward without neat endings honestly feels very real. It’s comforting in a strange way, to be reminded that uncertainty and incompleteness are part of being human.

A moving reflection on tension between promised progress and lived reality, this reminds us endurance, care and moral attention matter more than perfect outcomes. Your insight, that endurance rather than resolution is the true human triumph. The closing image of continuity, of ideas passing from one life to another- beautifully affirms that even in an unsettled world, hope survives in small, human acts.

Brilliant exposition of the essence of life embedded in “All`s Well That Ends Well ” play, Prof Tiwariji !

Your ingenuity of reflecting the characters and structure of play to modern world is par excellence !!

No doubt imperfect and unresolved, but acceptance of life as it is does not mean surrendering to fate or silencing aspiration; it means making peace with reality before trying to shape it. Cribbing drains energy without creating movement, while acceptance steadies the mind and restores agency. When we stop arguing with “what is,” we gain the clarity to act on “what can be.” Life rarely unfolds according to our preferences, but it always responds to our attitude. Acceptance is strength—the wisdom to conserve one’s inner fire, work with circumstances rather than against them, and grow without bitterness. In that calm acceptance, resilience is born, and progress becomes possible.

Happy New Year Sir,

This blog is a profoundly reflective piece. Your weaving of Dr. Kalam’s lived humility, Annie Johnson Flint’s hymn, and Shakespeare’s moral unease captures the quiet truth of our times—that life rarely resolves itself, yet demands endurance, conscience, and compassion. The reminder that meaning lies not in perfect endings but in persistence and responsibility is both unsettling and deeply consoling.

Thank you for this timely and humane reflection.

Warm Regards,

From a scientific perspective, acceptance is not passivity but cognitive alignment with reality. The brain functions most efficiently when it accurately models the environment before attempting to change it. Resistance in the form of chronic complaining or rumination consumes metabolic and attentional resources, activating stress pathways without producing adaptive action. Acceptance, by contrast, reduces cognitive friction, stabilises emotional regulation, and restores executive control.

When we stop contesting the facts of the present, the mind shifts from defensive reactivity to problem-solving mode. This recalibration enhances clarity, decision-making, and behavioural flexibility—key ingredients of effective action. Life may not conform to individual expectations, but outcomes are strongly influenced by mindset and response patterns. In this sense, acceptance is an intelligent conservation of energy: working with constraints rather than against them, transforming stress into learning, and adversity into adaptation. Resilience emerges not from denial or complaint, but from clear perception—and progress follows where perception is precise.

Life is imperfect by design, not by mistake. Its fractures create movement, learning, and choice; without them, existence would be static and sterile. Progress does not emerge from flawless systems but from human responses to uncertainty, error, and limitation. Our doubts provoke inquiry, our failures invite revision, and our vulnerabilities cultivate empathy. Technology may accelerate outcomes, but humanity gives them direction. Values, judgment, and responsibility arise only where perfection is absent. In embracing imperfection, we accept the role of stewards rather than masters of progress. What moves civilisation forward is not certainty, but the human capacity to adapt and care.

Dear Arunji, Profound and moving. This gently reminds us that endurance, not perfect resolution, is what gives life its meaning. Good one.

“Grace for the trials, help from above”….IT HAPPENS!

This exposition seamlessly weaves heritage, moral inquiry and contemporary experience, prompting deep appreciation for conscientious engagement and gentle perseverance.

Beautiful blog. You will live long beyond your life through your good works. As your co-author in India Wakes, I was glad to be along for the ride. Best wishes for a happy, healthy, and prosperous 2026.

Dear Arun ji, This is a beautifully honest reflection on life as it truly is—imperfect, unfinished, and often unresolved. The essay reminds us that meaning does not come from neat endings, but from the courage to continue, to endure, and to remain compassionate despite uncertainty. It resonates deeply because, in both personal lives and society at large, we learn not by arriving at perfect solutions but by learning to live thoughtfully within incompleteness—a quietly powerful piece.

Dear Prof., All is well that ends well – may 2026 bring you and your family joy! Like the Shakespearean Helena, you inspire so many of us to a purposeful and dignified living. Thank you for sharing your life with us through your writing and storytelling.