There is a peculiar magic in the things we eat—an intimacy so daily, so habitual, that it becomes almost invisible. Food enters our bodies the way air enters our lungs: without ceremony, without question. We assume its shapes, its colours, its textures, as though they...

A Book Between Generations

A Book Between Generations

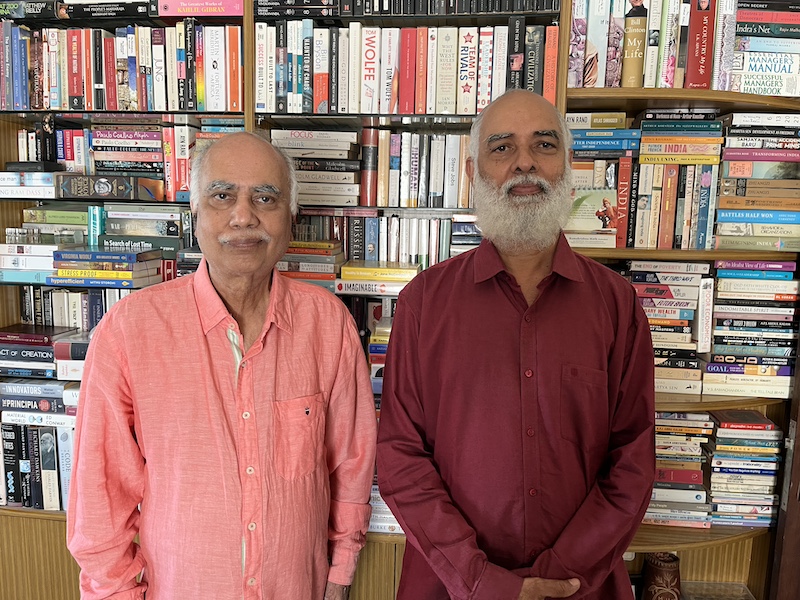

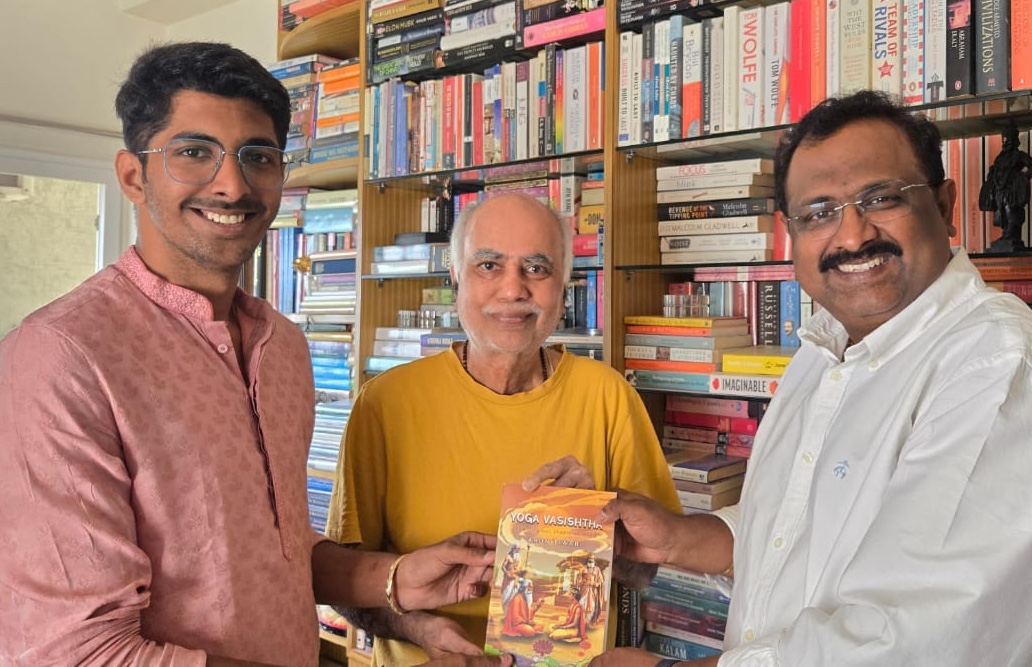

It was a mild noon, neither summer nor winter, when Venkat Kumar Tangirala came to see me. The sun, hidden behind clouds that held back its heat, allowed only a soft light, as if words were holding their breath between two thoughts, unsure whether to be expressed or remain silent. He arrived with his twenty-one-year-old son, Medhansh Tangirala, taller than his tall father, a young man with that familiar mixture of curiosity and hesitation which youth wears when stepping into a room of ideas.

Kumar Tangirala, of Brahminical ancestry, always the steady one, had in his eyes the mild exhaustion of someone who has travelled long, not just across distances but across the years. Medhansh, however, carried that unspent restlessness of beginnings—the kind that believes time is infinite and the world still pliant enough to bend to one’s will. As I greeted them, something stirred within me: a memory perhaps, or the faint echo of what it feels like to be twenty-one and sure that understanding lies just one book away.

We settled into conversation as easily as one slips into an old armchair. Kumar spoke of work and the state of things—his windmills, the confusion of tariff times, the noise—business became a relentless chase for something undefined. Medhansh listened, occasionally nodding, but I could sense his mind was elsewhere, moving through the invisible labyrinth of screens and opinions that define his generation’s consciousness.

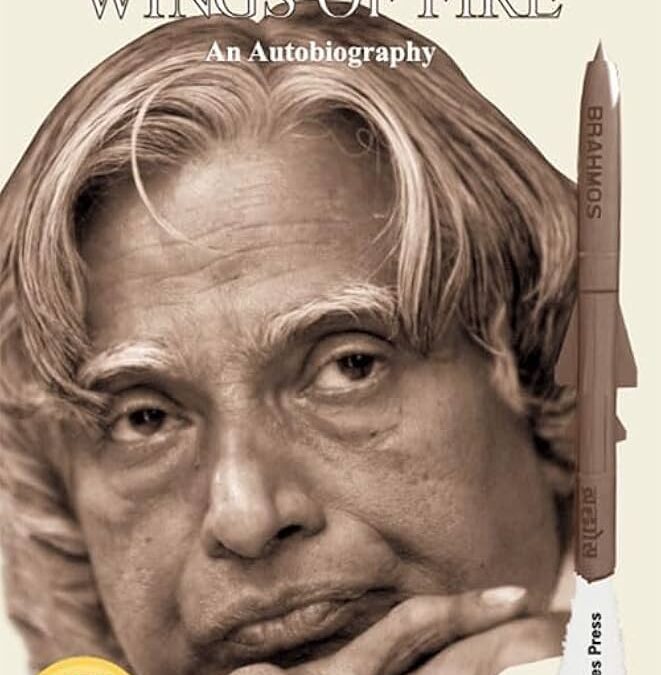

And then, I placed a copy of my new book, Yoga Vasishtha: The Original Thesis on Mind, before them. Its orange-yellow cover caught the light for a moment, like an idea surfacing from deep meditation. I said nothing for a while. The silence seemed to belong to the book itself, as though the centuries between Sage Vasishtha and us had folded into this one quiet moment in my living room.

Medhansh turned it in his hands. “Is it Rama sitting here? Is this philosophy or psychology?” he asked in a sincere, disoriented tone of one trying to map the borders of meaning. “It is both,” I replied. “And neither. It is a mirror. When you look into it, it shows not the world—but the mind that sees the world.”

He looked at me, perhaps expecting elaboration, but I smiled instead. There are moments when explanation kills the wonder it seeks to awaken. And Yoga Vasishtha—that vast, contemplative ocean of inquiry—demands wonder more than comprehension. It begins where the world ends and the mind begins to ask, What is real?

Kumar spoke then of how his son’s generation had been overwhelmed by the post-truth chaos—the endless tide of news, trends, and digital drama. “Medhansh says everyone has an opinion, but no one seems to know anything,” Kumar sighed. “I told him, maybe you should read something old enough to be new again.”

The sentence hung in the air, like incense. I felt its truth deeply. In a time when truth itself is fractured, the ancient voice of Vasishtha resonates with radical clarity once more. He doesn’t promise peace or salvation. He offers understanding—the quiet kind that dismantles illusion, not through belief, but through awareness.

I told the young man, “Look, Medhansh, this book is not to be read as one reads the news or a novel. It is to be entered into, like a forest. The more you wander, the more you lose the map—and in losing it, you begin to see differently.” Medhansh smiled faintly, half in politeness, half in intrigue. “But what is it about?” he asked. “It is about the mind,” I said. “The one thing we carry everywhere but rarely meet.”

As we spoke, I saw in him what I often see in young faces today—a subtle fatigue. The fatigue is not of labour but of attention. Attention that is stretched thin, pulled apart by devices, deadlines, and desires. In the post-truth world, where even silence is commodified, the mind rarely rests long enough to see itself. Yoga Vasishtha begins precisely there—at the threshold between restlessness and reflection.

Kumar looked at his son, perhaps remembering his own youth when questions still weighed and silence was still a language. “I think this will appeal to you,” he said. “It’s about the art of thinking, not about conclusions.

Medhansh nodded, holding the book as though it were a fragile relic from another time. I watched him and thought of Rama—the young prince in the scripture—disillusioned with the world, asking his teacher why life felt meaningless despite all its pleasures. That was the beginning of Yoga Vasishtha: a conversation between despair and wisdom. How fitting, I thought, that it should begin again here, between a father and his son.

Outside, the evening had deepened. The light was turning golden, spilling gently through the window, and for a moment it seemed that time itself had paused to listen. We spoke then of the relevance of ancient thought in modern times. I told them that philosophy, when lived, is not an escape but an awakening. It teaches discernment—the rarest virtue in an age where information masquerades as knowledge. The Vasishtha way is not to retreat to caves, but to live in the world with the stillness of one who knows that the waves and the ocean are not different.

Kumar asked softly, “Do you think young people can understand such depth?” I looked at his son, who was now tracing the Sanskrit title on the cover with his fingers. “They feel it,” I said. “Only the words haven’t come to them yet.”

Perhaps that is what Yoga Vasishtha offers—language for the inarticulate knowing that every young soul feels when it looks at the world and wonders, Is this all? The book tells us that the world we see is but the projection of the mind—shifting, shimmering, impermanent. It doesn’t condemn the illusion; it teaches us to see through it. In that seeing, freedom begins.

The conversation drifted, as all good ones do, into silences and digressions. Kumar spoke of his worries for the future, his son, and his confusion about what to believe. And I, quietly, thought of Vasishtha’s own words: “The mind is the cause of bondage and the mind is the cause of liberation.” It is that simple—and that difficult.

As they rose to leave, I felt a certain serenity. The book had found its next reader, or perhaps, its next questioner. I signed it with a few words: “May this not give you answers, but the courage to question rightly.”

Kumar clasped my hand warmly. “You always make even confusion sound noble,” he laughed in his trademark crackling manner. Medhansh smiled too, and I noticed that his eyes had softened, as if some veil had thinned, ever so slightly.

When they left, the house grew quiet again. I thought of the generations—how they come with their noise and their brilliance, their disbelief and their yearning. Each must find its own bridge between science and spirit, intellect and intuition. The mind remains the battlefield, as it was in Rama’s time, as it is now in the age of algorithms.

And so, the scene lingered in my mind long after the door closed: the father, the son, and the book between them. A trinity of time—the past, the future, and the eternal present—bound by a single question: What is real?

That is where Yoga Vasishtha: The Original Thesis on Mind begins—and where, perhaps, all modern minds must return.

MORE FROM THE BLOG

The Lost Wisdom of Our Kitchens

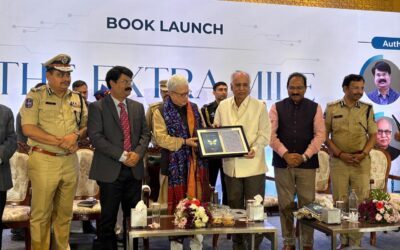

The Extra Mile

Shakespeare once reminded us that life is but a stage; listen closely, and beneath those familiar words, you can hear the soft hum of entrances and exits. Each of us arrives in medias res, as the Latins say—dropped into the middle of a vast, unfolding drama whose...

The Theatre Within

I have been fascinated by Shakespeare, as most of those fancy English phrases and words that enchanted me were created by this one man who lived in England during 1564–1616. I was always intrigued by how one individual could produce such a great body of work that...