Still in her twenties, Rebecca F. Kuang has emerged as one of the most incisive literary voices examining empire’s afterlives. Born in China, raised in the United States, and educated at Cambridge and Oxford, she broke through with The Poppy War, a novel rooted in...

The Lost Wisdom of Our Kitchens

The Lost Wisdom of Our Kitchens

There is a peculiar magic in the things we eat—an intimacy so daily, so habitual, that it becomes almost invisible. Food enters our bodies the way air enters our lungs: without ceremony, without question. We assume its shapes, its colours, its textures, as though they were born complete, needing no history, no explanation. But if we slow ourselves down, if we choose for a moment to observe, not with the hurried mind of our age but with a gentler, lingering gaze, then even the simplest ingredient begins to shimmer with hidden worlds. The kitchen, then, reveals itself as a quiet laboratory; each jar, each seed, each crystal becomes a phenomenon; and even a humble sweet—say, a shard of rock sugar—turns into a secret waiting to be understood.

The other evening, after finishing dinner at a small neighbourhood eatery, I was offered the familiar combination of saunf (fennel seeds) and mishri (rock sugar)—that tiny ritual that so many Indian meals conclude with. On a whim, I turned to my host, a software engineer, and asked whether he knew what mishri really was: how those transparent little crystals form, what process gives them their clarity and crunch. He looked at me with a strange mixture of amusement and discomfort. His gaze seemed to say, “What a ridiculous question!”, yet beneath it flickered the soft embarrassment of ignorance. It struck me then how rare it is, in our modern lives, to pause and wonder about the simplest things we consume.

The next morning, as I stood waiting for my tea water to boil, the memory of his expression returned. I watched the bubbles form at the bottom of the steel vessel, the tea leaves bloom in the rolling water, and suddenly the place seemed transformed. A kitchen is, in fact, a laboratory—not merely a site of cooking, but of transformations. Ingredients are never inert; they swell, dissolve, brown, align, pop and crystallise. They obey laws as ancient as the earth itself, yet sit quietly in jars and tins, asking nothing more than a moment’s attention.

My eyes drifted to the row of boxes on the rack, filled with the materials used to cook a meal. There was also a container of mishri. How strange, I thought, that something so unassuming, so crystal clear, should contain within it such a profound lesson in science. A piece of rock sugar is not a mere sweet; it is a slow story of molecules organising themselves into an ordered lattice, a three-dimensional poem written in the language of thermodynamics. How many marvels, then, have we swallowed unthinkingly? How many stories have dissolved on our tongues without ever being heard?

Crystallisation is at the very heart of material science, and what could be a simpler example than rock sugar? When hot sugar syrup cools, it enters a fragile state of supersaturation. In that suspended moment, a few sucrose molecules—almost shyly—align themselves, forming tiny nuclei. Around these seeds, the crystal grows, layer by layer, face by face, each plane a response to molecular geometry and thermal history. Slow cooling yields larger, clearer crystals; rapid cooling yields scattered grains and opacity. The same principles shape salt in the desert, snowflakes in winter, and even the flawless silicon crystals that carry the weight of modern computing. Yet, here they are, forming quietly in a pan in our kitchens.

This curiosity, once awakened, drifts effortlessly toward other ingredients. Sabudana (tapioca pearls), for example, is not merely a fasting food but a living demonstration of starch science. Starch granules are tiny, semi-crystalline bodies. When heated with water, they swell, burst, and transform into a gel—a process called gelatinisation. This gel is rolled into pearls, dried, and polished into the soft white orbs we soak before cooking. A sabudana pearl, so innocent in appearance, is really a tiny globe of polymer behaviour, viscoelasticity and phase transition.

Then there is makhana, the fox nut, born from the lotus seed and reborn in the pan. Inside its hard shell lies a matrix of starches and proteins. As the seed is roasted, moisture trapped in its heart expands into steam; at the precise moment when internal pressure overcomes rigidity, the entire structure bursts open. The seed becomes a puff—light, airy, delicately porous. This is not mere cooking; it is a controlled explosion, a marvel of thermal expansion, pressure thresholds and structural transformation.

And yet, I thought, our inquiry could not end with individual ingredients alone. It must extend to the collective wisdom that once guided our festive foods. Just then—like a fragrance drifting in from an old courtyard—the memory of my grandmother surfaced. I could see her, hands steady and sure, making sweets that changed with the seasons. In winter, she stirred ghee-laden laddoos with edible gum and dried ginger for warmth; in summer, she shaped cooling khus-khus (poppy seeds) and coconut preparations; during festivals, she crafted confections with herbs, nuts, lotus seeds and spices, each one carrying a purpose beyond taste. These sweets were not indulgences alone; they were nutritional equations, cultural stories and seasonal prescriptions. A whole science lived in her hands, though she never named it so.

Traditional Indian sweets were once astonishing compositions of edible gums, herbs, spices, nuts, seeds and grains—each chosen not only for taste but also for their physiological effects. Gond (edible gum) for strength, dried ginger powder for warmth, nutmeg for calm, cardamom for digestion, khus-khus for cooling, and til (sesame seeds) for vitality. A laddoo (a ball-shaped confection) was a miniature medicinal ecosystem; a barfi (fudge candy) was as much a work of biology as of cuisine. These were not random mixtures but carefully balanced systems shaped by generations of observation, trial, memory and intuition.

Today, much of this quiet intelligence has been swept aside by the tide of convenience. Industrial sweets dominate our markets—gleaming, colourful, symmetrical, long-lasting. But this kind of perfection carries a quiet cost beneath its sheen. Artificial colours impersonate saffron; synthetic flavours mimic rose and pistachio; stabilisers, emulsifiers and preservatives grant unnatural shelf life; glucose syrups replace slow-cooked jaggery; hydrogenated oils masquerade as ghee. These sweets are as much chemical engineering as they are food—attractive but nutritionally hollow, convenient but quietly harmful. In the quest for texture and durability, we have lost nourishment and knowledge.

This is why curiosity matters. To ask, “What is this? How is it made? Why was it once done differently?” is to reclaim not only our health but also our heritage. When we ask such questions, mishri becomes a lesson in crystallisation; sabudana, one in polymer science; makhana, one in thermal mechanics; and traditional sweets, one in cultural engineering.

Walk into a kitchen with this awareness, and it transforms. The jars become textbooks; the spices, experiments; the utensils, instruments. One begins to see that the everyday act of cooking is a dialogue between the natural world and human wisdom. In this quiet, reflective state, the kitchen becomes both laboratory and temple—a place where matter transforms and meaning emerges.

And perhaps that is the real sweetness behind all these sweet things: not just in their taste, but in their story. When we choose to look closely, we discover that even the smallest crystal of mishri contains a universe—one that is ours to explore. After all, is not the highest endowment of humankind the twin power of imagination and curiosity? If we forsake them, what a royal squandering of our finest inheritance it would be! For life is meant to be observed, examined and questioned—not sleepwalked through in the dim hallway of habit.

MORE FROM THE BLOG

Empire Without Flags

A Child and a Name in the Lila of Becoming

My younger brother Salil Tiwari’s son, Sudhanshu, and his wife, Stuti, have been blessed with a son. They live in Meerut, my hometown, and visited me recently. Like all visits involving a newborn, it carried a quiet gravity—soft footsteps, hushed voices, time slowing...

Life Goes On—Imperfect and Unresolved

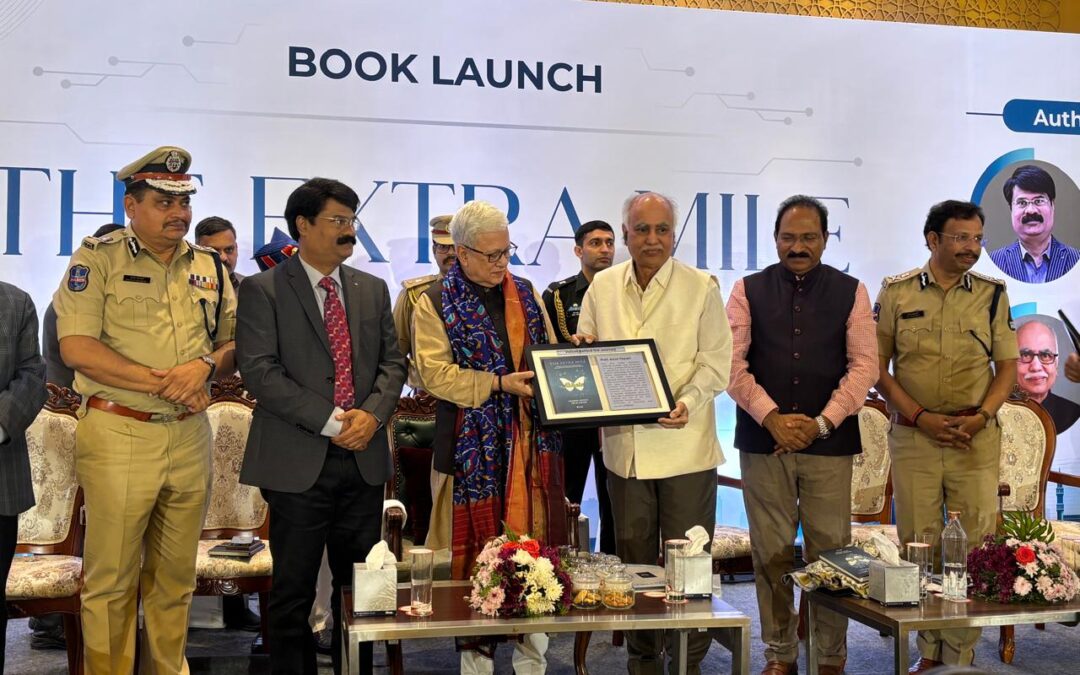

The readers have lapped up the silver jubilee edition of Wings of Fire. Within a month of its release on October 15, 2025, the 94th birth anniversary of Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, the first print was sold out. At the 38th Hyderabad Book Fair, on December 20th, 2025, I saw...