The Lost Wisdom of Our Kitchens

There is a peculiar magic in the things we eat—an intimacy so daily, so habitual, that it becomes almost invisible. Food enters our bodies the way air enters our lungs: without ceremony, without question. We assume its shapes, its colours, its textures, as though they were born complete, needing no history, no explanation. But if we slow ourselves down, if we choose for a moment to observe, not with the hurried mind of our age but with a gentler, lingering gaze, then even the simplest ingredient begins to shimmer with hidden worlds. The kitchen, then, reveals itself as a quiet laboratory; each jar, each seed, each crystal becomes a phenomenon; and even a humble sweet—say, a shard of rock sugar—turns into a secret waiting to be understood.

The other evening, after finishing dinner at a small neighbourhood eatery, I was offered the familiar combination of saunf (fennel seeds) and mishri (rock sugar)—that tiny ritual that so many Indian meals conclude with. On a whim, I turned to my host, a software engineer, and asked whether he knew what mishri really was: how those transparent little crystals form, what process gives them their clarity and crunch. He looked at me with a strange mixture of amusement and discomfort. His gaze seemed to say, “What a ridiculous question!”, yet beneath it flickered the soft embarrassment of ignorance. It struck me then how rare it is, in our modern lives, to pause and wonder about the simplest things we consume.

The next morning, as I stood waiting for my tea water to boil, the memory of his expression returned. I watched the bubbles form at the bottom of the steel vessel, the tea leaves bloom in the rolling water, and suddenly the place seemed transformed. A kitchen is, in fact, a laboratory—not merely a site of cooking, but of transformations. Ingredients are never inert; they swell, dissolve, brown, align, pop and crystallise. They obey laws as ancient as the earth itself, yet sit quietly in jars and tins, asking nothing more than a moment’s attention.

My eyes drifted to the row of boxes on the rack, filled with the materials used to cook a meal. There was also a container of mishri. How strange, I thought, that something so unassuming, so crystal clear, should contain within it such a profound lesson in science. A piece of rock sugar is not a mere sweet; it is a slow story of molecules organising themselves into an ordered lattice, a three-dimensional poem written in the language of thermodynamics. How many marvels, then, have we swallowed unthinkingly? How many stories have dissolved on our tongues without ever being heard?

Crystallisation is at the very heart of material science, and what could be a simpler example than rock sugar? When hot sugar syrup cools, it enters a fragile state of supersaturation. In that suspended moment, a few sucrose molecules—almost shyly—align themselves, forming tiny nuclei. Around these seeds, the crystal grows, layer by layer, face by face, each plane a response to molecular geometry and thermal history. Slow cooling yields larger, clearer crystals; rapid cooling yields scattered grains and opacity. The same principles shape salt in the desert, snowflakes in winter, and even the flawless silicon crystals that carry the weight of modern computing. Yet, here they are, forming quietly in a pan in our kitchens.

This curiosity, once awakened, drifts effortlessly toward other ingredients. Sabudana (tapioca pearls), for example, is not merely a fasting food but a living demonstration of starch science. Starch granules are tiny, semi-crystalline bodies. When heated with water, they swell, burst, and transform into a gel—a process called gelatinisation. This gel is rolled into pearls, dried, and polished into the soft white orbs we soak before cooking. A sabudana pearl, so innocent in appearance, is really a tiny globe of polymer behaviour, viscoelasticity and phase transition.

Then there is makhana, the fox nut, born from the lotus seed and reborn in the pan. Inside its hard shell lies a matrix of starches and proteins. As the seed is roasted, moisture trapped in its heart expands into steam; at the precise moment when internal pressure overcomes rigidity, the entire structure bursts open. The seed becomes a puff—light, airy, delicately porous. This is not mere cooking; it is a controlled explosion, a marvel of thermal expansion, pressure thresholds and structural transformation.

And yet, I thought, our inquiry could not end with individual ingredients alone. It must extend to the collective wisdom that once guided our festive foods. Just then—like a fragrance drifting in from an old courtyard—the memory of my grandmother surfaced. I could see her, hands steady and sure, making sweets that changed with the seasons. In winter, she stirred ghee-laden laddoos with edible gum and dried ginger for warmth; in summer, she shaped cooling khus-khus (poppy seeds) and coconut preparations; during festivals, she crafted confections with herbs, nuts, lotus seeds and spices, each one carrying a purpose beyond taste. These sweets were not indulgences alone; they were nutritional equations, cultural stories and seasonal prescriptions. A whole science lived in her hands, though she never named it so.

Traditional Indian sweets were once astonishing compositions of edible gums, herbs, spices, nuts, seeds and grains—each chosen not only for taste but also for their physiological effects. Gond (edible gum) for strength, dried ginger powder for warmth, nutmeg for calm, cardamom for digestion, khus-khus for cooling, and til (sesame seeds) for vitality. A laddoo (a ball-shaped confection) was a miniature medicinal ecosystem; a barfi (fudge candy) was as much a work of biology as of cuisine. These were not random mixtures but carefully balanced systems shaped by generations of observation, trial, memory and intuition.

Today, much of this quiet intelligence has been swept aside by the tide of convenience. Industrial sweets dominate our markets—gleaming, colourful, symmetrical, long-lasting. But this kind of perfection carries a quiet cost beneath its sheen. Artificial colours impersonate saffron; synthetic flavours mimic rose and pistachio; stabilisers, emulsifiers and preservatives grant unnatural shelf life; glucose syrups replace slow-cooked jaggery; hydrogenated oils masquerade as ghee. These sweets are as much chemical engineering as they are food—attractive but nutritionally hollow, convenient but quietly harmful. In the quest for texture and durability, we have lost nourishment and knowledge.

This is why curiosity matters. To ask, “What is this? How is it made? Why was it once done differently?” is to reclaim not only our health but also our heritage. When we ask such questions, mishri becomes a lesson in crystallisation; sabudana, one in polymer science; makhana, one in thermal mechanics; and traditional sweets, one in cultural engineering.

Walk into a kitchen with this awareness, and it transforms. The jars become textbooks; the spices, experiments; the utensils, instruments. One begins to see that the everyday act of cooking is a dialogue between the natural world and human wisdom. In this quiet, reflective state, the kitchen becomes both laboratory and temple—a place where matter transforms and meaning emerges.

And perhaps that is the real sweetness behind all these sweet things: not just in their taste, but in their story. When we choose to look closely, we discover that even the smallest crystal of mishri contains a universe—one that is ours to explore. After all, is not the highest endowment of humankind the twin power of imagination and curiosity? If we forsake them, what a royal squandering of our finest inheritance it would be! For life is meant to be observed, examined and questioned—not sleepwalked through in the dim hallway of habit.

MORE FROM THE BLOG

A Child and a Name in the Lila of Becoming

My younger brother Salil Tiwari’s son, Sudhanshu, and his wife, Stuti, have been blessed with a son. They live in Meerut, my hometown, and visited me recently. Like all visits involving a newborn, it carried a quiet gravity—soft footsteps, hushed voices, time slowing...

Life Goes On—Imperfect and Unresolved

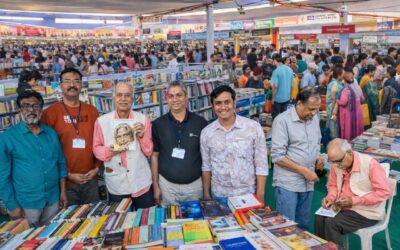

The readers have lapped up the silver jubilee edition of Wings of Fire. Within a month of its release on October 15, 2025, the 94th birth anniversary of Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, the first print was sold out. At the 38th Hyderabad Book Fair, on December 20th, 2025, I saw...

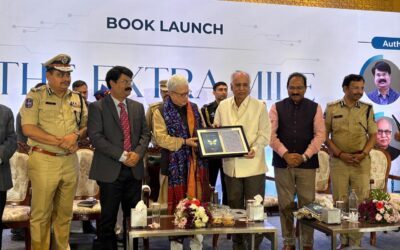

The Extra Mile

Shakespeare once reminded us that life is but a stage; listen closely, and beneath those familiar words, you can hear the soft hum of entrances and exits. Each of us arrives in medias res, as the Latins say—dropped into the middle of a vast, unfolding drama whose...

Arunbhai, i looked at food with an eye of taste, aroma, texture and nutrition. You’re a great scientist, hence you’re looking through a scientific eye. What an amazing and interesting aspect to look

food at! Very interesting, until now I never dwelled into the way you have mentioned about food! Simple food, traditional food made with Grandma’s recipes at home definitely fulfills our stomachs. It is satisfying to the mind and body! As there is a saying “Yeh Chane ki dal, yeh chane ki roti, jab khayega tab bhukh jayegi!” In the era of fast foods, the “hunger” (the bhukh) never goes away. Whatever we eat has a chemical reaction that affects our wellbeing. Some experts say that the food we eat daily must be eaten as “medicine”. Thank you bhaiya

Fascinating insight into culinary arts and science, Prof Tiwariji! Your subtle wakeup call about losing the collective wisdom that guides food is very apt in the era of convenience!!

Traditional cooking is a quiet laboratory refined over centuries. Fermentation in curd, idli, and dosa enhances the growth of gut-friendly microbes and improves mineral absorption. Slow cooking on gentle heat preserves nutrients while making complex foods easier to digest. Spices such as turmeric, cumin, pepper, and ginger are not merely flavouring agents; they are natural antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, and digestive catalysts, used in precise combinations to balance the body. The sequence of tempering—oil, seeds, aromatics—optimises bioavailability of fat-soluble compounds. Long before modern nutrition science, kitchens functioned as intuitive research centres, aligning taste, health, seasonality, and human physiology into a single nourishing practice.

I am baffled and amused by those who think there is no science and skill behind traditional cooking. And I am yet to enjoy the gastronomy of rapid fixes that we are slowly replacing our traditional cooking with. I have stubbornly refused to let go, of some of these cooking methods/ingredients/recipes and I try to pass the same to my children albeit with some level of resistance, but with time and patience, I see the logic sinking in. Those little milestones will make a big difference in time.

Cooking is as much science as it is art. The art lies in intuition—knowing how flavours combine, when to adjust heat, how a dish should look, smell, and feel. The science lies beneath it all: how heat transforms proteins, how acids balance fats, how spices release oils, how fermentation improves nutrition, and how timing alters texture and taste.

Every good meal is an experiment guided by experience. Boiling, roasting, tempering, fermenting, and slow cooking—each method follows physical and chemical principles. Spices are not added at random; they are chosen for their interactions with ingredients and with the body. Traditional cuisines mastered this science long before laboratories named it.

Yet cooking is never mechanical. Two people can follow the same recipe and produce different results, because art lives in attention, care, and creativity. Science ensures consistency and nourishment; art brings joy, memory, and identity.

When science and art meet in the kitchen, food becomes more than sustenance—it becomes health, culture, and connection.

Sir,

रोज़ाना खाना बनाने में मसालों और जड़ी-बूटियों का इस्तेमाल करना नैचुरली हेल्दी रहने का सबसे आसान तरीका है। पारंपरिक किचन यह समझते थे कि खाना सिर्फ़ स्वाद के लिए नहीं, बल्कि बैलेंस और हीलिंग के लिए भी होता है। हल्दी, अदरक, लहसुन, जीरा, काली मिर्च, धनिया, और तुलसी और करी पत्ते जैसी जड़ी-बूटियाँ धीरे-धीरे पाचन, इम्यूनिटी और मेटाबॉलिज़्म को सपोर्ट करती हैं।

ये चीज़ें चुपचाप काम करती हैं—सूजन कम करती हैं, पेट की सेहत सुधारती हैं, और शरीर के नैचुरल बचाव को मज़बूत करती हैं। जब इनका रेगुलर इस्तेमाल किया जाता है, तो ये कई छोटी-मोटी समस्याओं को बड़ी बीमारियों में बदलने से रोकती हैं। असली मसालों के साथ खाना बनाना कोई पुरानी आदत नहीं है जिसे रोमांटिक बनाया जाए; यह पीढ़ियों से मिली प्रैक्टिकल समझदारी है।

जब किचन समझदार होता है, तो शरीर मज़बूत रहता है—और डॉक्टरों की ज़रूरत कम पड़ती है, इसलिए नहीं कि दवा को मना किया जाता है, बल्कि इसलिए कि हर दिन, एक-एक करके, सेहत बनाए रखी जाती है।

Hon’ble Arun sir, Thanks a lot for writing such an informative blog on historical Kitchen magic. So many examples quoted are very informative and interesting. Many people do not know how Mishri, Saboodana, and Makhana are made, even Salt, especially Shambar (a town in Jaipur district of Rajasthan), and Crystal salt. We still prepare many dishes mentioned in the blog, particularly Ladoo with Deshi Ghee, edible gum, ginger powder, ajwain powder, fenugreek powder, wheat flour, and jaggery (mishri or sugar). The final product has a great taste and acts like a home-made medicine, removing toxins from the body and boosting immunity. In fact, the kitchen was so strong in the earlier period, providing everything, but today we are losing and are more dependent on ready-made dishes, many of which are impure and unhealthy.

Thanks and regards

Once again, kudos to your breadth of interests as well as inquisitiveness Sir. You’ve turned the kitchen into a science class.

Dear Sir, Greetings! This is a wonderfully illuminating piece that restores dignity to everyday knowledge we often overlook. By blending science, culture, and lived memory, you remind us that authentic learning begins with curiosity and observation—even in the most familiar spaces like our kitchens. The way you connect crystallisation, starch science, and thermal principles with traditional food practices makes this both intellectually enriching and deeply human. It is heartening to see scientific thinking presented not as abstraction, but as wisdom embedded in daily life and inherited tradition. Writing like this does more than inform—it awakens the learner’s mind. Very well written, great. Warm Regards.

Traditional cooking was not sentimental or superstitious. It was empirical. Methods such as soaking, fermenting, slow cooking, tempering spices in fat, and combining foods thoughtfully were all responses to how the human body actually works. Indigenous oils, whole grains, real spices, and patient preparation were technologies—low-cost, low-energy, and remarkably precise.

The erosion of this knowledge is alarming not only because it affects taste, but because it affects health at a population scale. Rising metabolic disorders, gut dysfunction, and inflammatory diseases are not disconnected from the loss of culinary intelligence. When food becomes chemistry rather than culture, nourishment becomes an afterthought.

Returning to traditional kitchens is not an emotional retreat into the past. It is a rational return to systems that evolved in dialogue with human biology and local ecology. It is an act of public health, environmental responsibility, and cultural continuity. Reclaiming this wisdom is no longer optional nostalgia; it is an essential correction—one that restores food from an industrial commodity back into a source of life, resilience, and quiet well-being.

Our kitchens were once living laboratories of health, intuition, and ecological intelligence. What we cooked, how we cooked, and when we cooked were guided not by labels or advertisements, but by accumulated wisdom—seasonal rhythms, bodily responses, and a deep respect for ingredients. That wisdom is quietly slipping away.

Today, food has become an industrial product long before it reaches our plates. Chemicals are added at every stage: cultivation relying on synthetic inputs, processing aimed at shelf life rather than nutrition, oils refined to cause metabolic confusion, sugars removed from context and fibre, and spices diluted or replaced with artificial flavours. Even cooking itself is increasingly mediated by shortcuts that prioritise speed, uniformity, and cost over digestion and balance. What seems convenient is often biologically costly.

Thank you Sir for sharing this wonderful, thought-provoking blog.

It made me stop and think about how little attention I usually give to the food I eat every day. The moment with the mishri after dinner felt very real. I could picture that pause, that awkward smile, and the question hanging in the air. The part about your grandmother especially stayed with me. It reminded me of the quiet confidence our elders had in the kitchen, a gift that generation carried and made it look so effortless.

The piece reminds one that the kitchen was our first university—and curiosity its original curriculum. Who knew a bowl of saunf and mishri could outperform most STEM classrooms? This piece gently exposes the irony of our times: we code algorithms for a living yet cannot decode the science simmering in our own kitchens. What you show so beautifully is that tradition was never anti-science—it was science practiced with patience and humility. Our ancestors didn’t publish papers; they published laddoos, barfis,—peer-reviewed by generations. This is material science with a grandmother’s blessing, a rare reminder of the laws of thermodynamics once lived comfortably alongside intuition and care and also shows that knowledge need not wear a lab coat to be rigorous.

Wonderful Arun ji, I loved how this piece made me stop and notice what I usually take for granted — the simple act of cooking and eating. There is a deep intimacy in the kitchen, in choosing ingredients with care, in honouring the traditions that nourish both body and soul. Your writing revived that lost wisdom for me, inviting me to slow down and reconnect with the heart of our homes. Thank you for this beautiful reminder.

Interesting Arunji. The “mishri” problem is something that I did encounter very recently and so glad to see it being dealt with so much science, culture and fascination here. And on the health, art and science of kitchen, while metros have significantly outsourced it to commercialization, feeling relieved that villages still have many of these aspects very much alive.

Finally, this article reminded me of a perspective I heard many years back – to understand a family check out its kitchen. Understanding “who” cooks, “when”, “what”, “for whom” and “how much” is cooked can answer many deep questions about the family which at times we may not be able to imagine.

The art and science of cooking in olden societies and cultures got refined to the highest degree of sophistication. Kitchen is in fact the center of the house. In nomadic societies everything circles around kitchen. And then our mothers and grannies always had that special touch which their progenies carry in their DNA. My children who are scattered around the world travel long distances just to have that Kadhi- Chawal which only their mother can make.

A magnificent meditation on everyday science. You turn the kitchen into a classroom, the sweet into a syllabus, and curiosity into a moral act. This piece beautifully reminds us that tradition is not superstition but accumulated intelligenc…and that to wonder is to truly taste life, not merely consume it.

Arunji, this blog reminds us that the kitchen is not just a place of routine, but a living classroom of science, culture, and memory. By tracing mishri, sabudana, and makhana back to their molecular and seasonal wisdom, the blog gently exposes how much knowledge we consume without noticing.

It’s a quiet but powerful invitation to slow down, to question, and to reclaim the intelligence embedded in traditional foods before convenience erases it. I enjoy watching lost recipes on TV and trying my hand at some of those!