Yoga Vasishtha Walks into Nolan’s Dream

I watched Christopher Nolan’s Inception when it was released in 2010, back when going to the theatre still felt like an event. The film is centred around the idea of entering and manipulating dreams, slipping into layers of the mind as easily as walking through doors. In that world, the only reliable test for what is real is a small spinning top: it falls in reality, but in a dream, it spins endlessly. When the film ended, I stayed in my seat as the credits faded and the screen turned dark. I didn’t fully understand what I had just seen, yet it held me completely. It felt as if I, too, was left hanging between two worlds, just like the final top that wobbles but never reveals the truth.

It was in such a moment—breath held between realities—that I heard a whisper. Not the soft murmur of Hollywood, but the calm voice of Vasishtha Muni, guiding the young prince Rama in a world just as uncertain, though untouched by our screens and cities.

Two worlds, separated by time, touched in that hush after the credits. What Nolan filmed with architecture and mirrors, Vasishtha painted with words and silence. Both asked us the question we fear the most—What if everything we call real is but a dream of the mind? And suddenly, cinema dissolves, and the scripture breathes.

Imagine a thin sheet of light hanging in the air. Then another settles over it, and then another, until hundreds of soft, see-through layers glow gently on top of each other. Try, if you can, to tell which veil came first, and which followed; which is the original and which is only a reflection. Impossible? That is how the world feels in Inception—layers folding into layers, dreams rippling beneath deeper dreams, and reality slipping like silk between the fingers.

We, too, grew up in such dreams. Our childhood longings mingle with another’s yearnings; together, they weave a new fabric of shared hopes, fears and compromises. Two adults marry, harbouring their individual dreams. When children arrive, they bring their own embryonic worlds to manifest. As they grow, love, and choose partners, more dreams enter the tapestry—strange, beautiful, conflicting. Soon, the house is full of overlapping universes: ambitions brushing against disappointments, laughter spilling over silence, tenderness meeting fatigue.

And somewhere in that swirl, you pause, bewildered. You watch people adjust, resist, laugh, quarrel, surrender, and rise again—actors in a play they did not write, yet feel compelled to perform. You begin to doubt what is real. Was that happiness or habit? Anger or exhaustion? Was that a promise or simply a line rehearsed too often to question?

Veil after veil. Dream upon dream. And at the heart of it all, a quiet whisper: What is the waking world, and when did I fall asleep? And is this not what Vasishtha Muni said to young prince Rama?

“This world is as real as the dream you see every night.” (Yoga Vasishtha 7.168.20).

A gentle sentence, terrifying in its simplicity. The words sound so true when I, now 70 years old, sit on the ledge of memory, unable to tell whether I stand on solid ground or the edge of a subconscious abyss.

In the film Inception, we see cities rise and collapse, time stretch, and staircases loop — the mind building worlds as effortlessly as a child breathes. Valmiki captured this much earlier in the Yoga Vasishtha, which he wrote after the Ramayana: “Every thought shapes a universe” (4.4.15). Queen Chudala becomes a young monk boy, Kumbha, to test her husband, Shikhidkwaja; Lila meets another Lila from a future life. King Gadhi turns into a Chandala. Four clones of Vipaschit spring up, each living differently and transmigrating into different loops. Every emotion seeds a reality. It is not merely a filmic trick; it is metaphysics with a pulse.

But before you call it a puppet show, there is no puppeteer here. Like Cobb in the film, we are followed not by policemen but by our past—our guilt crystallised into the exquisite and dangerous form of Mal, Cobb’s wife. She enters every dream, slicing the fabric of illusion, not to set him free, but to drown him deeper in his own remorse. We all live the scripts we ourselves write, but wonder when they roll out as our fate. How brilliantly the Yoga Vasishtha created the scene in the palace of Ayodhya: a teenage Rama, back from a pilgrimage, haunted by the question: What is the point of this world? Why do we suffer, love, lose, wage war, dream, and despair?

Memory binds the human mind. A prince and a thief, a royal and a fugitive, a billionaire and a pauper—all sit captive in the chambers of their own minds. Vasishtha Muni murmurs, like a wind through leaves, “The impure and confused mind, haunted by the ghost of multiplicity, creates a world of duality and illusion” (6.23.21). And so, Nolan shows us a man sinking in his subconscious oceans; Vasishtha shows us a world sunk in illusion’s tide. Both speak not merely to kings and dream-thieves, but to each of us whose heart has tripped over a memory and never recovered its footing.

In Inception, Ariadne, a collaborator of Cobb, draws bridges, buildings and labyrinths. In the Yoga Vasishtha, the architect is the mind itself. Not a team of designers, but a single pulse of consciousness shapes mountains, raises civilisations, and sets galaxies turning like a dancer’s lehnga. None is more real than the appearance and dispersion of ripples in a pond right before one’s eyes. Both works teach us—softly, dangerously—that we are builders, and weavers of our own dreams.

Cobb carries his totem—a tiny spinning top, trembling with truth. If it falls, he is awake—safe. If it spins forever, he is living in a dream. But what of us, who carry no such delicate instrument? What totem do we place on our tables when the morning news feels theatrical and our own thoughts echo louder than the world outside?

Vasishtha Muni offers not a spinning object, but a still awareness. The witness. That which sees both waking and dream, and remains untouched. One looks outward—a top trembling on wood. The other looks inward—consciousness watching itself. In the end, even Cobb’s totem betrays him, as all external anchors must. But the witness never falters, because it is not in the scene. It is the silent observer behind it.

Long before modern psychology sketched the first map of the psyche, before Freud named the unconscious or William James classified the flow of thought, an ancient Indian text sat in quiet majesty, speaking of the mind with a precision and daring unmatched even today. In the Yoga Vasishtha, thought is not merely a function of brain matter; it is the sovereign architect of reality. Consciousness is not a by-product—it is the field in which worlds rise and fall like ripples in a boundless lake.

Centuries before science coined terms like cognitive bias, mental conditioning, neuroplasticity and simulation, the sages of India had already walked those inner corridors. They observed, not with instruments, but with piercing stillness and disciplined awareness. They asked: What is perception? How does desire distort cognition? How does memory fabricate identity? What is the root of suffering? What is the nature of reality when the mind ceases? And they answered not in riddles, but with astonishing psychological clarity.

“The mind is nothing but a field of feelings.” (Yoga Vasishtha 3.96.1)

The next time you dream, pause and wonder: what if a dream is not a casual pastime gifted by sleep? Seek a faint glimmer of awareness inside the dream. What if the dream is not something you watch, but something that watches you? What if it is showing you a mirror, asking you to notice how your own actions and habits shape the flow of your mind, turning small vibrations into situations, emotions, and even destiny?

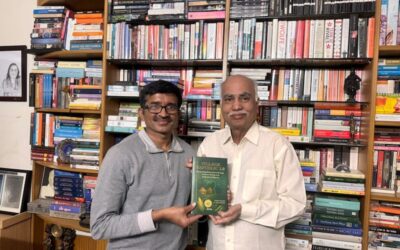

This was my intention in writing Yoga Vasishtha: The Original Thesis on Mind — to free this timeless science from the confines of Sanskrit verse and place it gently, yet urgently, in the hands of young minds searching for clarity in our bewildering age.

When I say there are no colours in reality—only electromagnetic frequencies your brain translates into colour—it can feel unsettling. We are enchanted by this vivid palette, yet it is a construct, a sensory illusion. So too with the world and the cosmos: they exist only in the seeing and in the sensing. When the eyes finally close, that private universe dissolves. The credits roll; the screen goes blank; and the theatre empties. At that point, what does it matter how brilliant or terrible the film once seemed?

MORE FROM THE BLOG

Science, Service, and the Long Goodbye to Leprosy

It was already evening when they arrived, and I sensed a good feeling. The light had softened, retreating gently from the edges of objects, as though the day itself wished to listen to what came next. Dr. Gangadhar Sunkara came with Dr. Chinnababu Sunkavalli—both...

Empire Without Flags

Still in her twenties, Rebecca F. Kuang has emerged as one of the most incisive literary voices examining empire’s afterlives. Born in China, raised in the United States, and educated at Cambridge and Oxford, she broke through with The Poppy War, a novel rooted in...

A Child and a Name in the Lila of Becoming

My younger brother Salil Tiwari’s son, Sudhanshu, and his wife, Stuti, have been blessed with a son. They live in Meerut, my hometown, and visited me recently. Like all visits involving a newborn, it carried a quiet gravity—soft footsteps, hushed voices, time slowing...

Greetings for putting forward mesmerizing similarities into philosophical insight of Yog-Vashistha scriptures & Christopher Nolan film inception revealing illusionary nature of the world.. is a topic fewest will dare to write & comment..

Thanks for opening to new field of ancient science in sanskrit scriptures for young minds..

A breathtakingly erudite meditation that sutures Hollywood’s dreamscapes with India’s timeless metaphysics. Your writing is a rare symphony of intellect and imagination.

Dear Sir, Greetings! This was a profoundly beautiful piece. I loved how you wove Nolan’s dream architecture with the timeless teachings of Yoga Vasishtha. The parallels you drew between cinematic illusion and inner consciousness felt seamless and deeply moving. Thank you for opening up an entirely new way of seeing both the film and the scripture. Warm Regards,

Dear Arun ji, This piece beautifully weaves ancient wisdom with modern imagination. I loved how Yoga Vasishtha and Nolan’s dream-world were brought together so seamlessly. It reminds us that the human mind has always searched for meaning — across scriptures, stories, and cinema. Reading this felt like a gentle nudge to look within, to explore the deeper layers of our own consciousness. Thank you for connecting timeless philosophy with today’s world in such an engaging way.